The Ed Tech and Makerspace movements ask teachers to learn alongside our students more than ever before. This results in many classrooms being facilitated through some version of informal conferencing, where all the students (either on their own or in groups) are working on a task while the teacher floats between groups assessing understanding, helping students overcome struggles, and providing guidance for meaningful extensions of the day’s learning objectives.

But our classrooms are still full of diverse learners and it is incredibly difficult to support all of our learners at their level when we are learning alongside them. Luckily, we educators have at least one big advantage: We’re adults.

We’ve lived through life, amassed a variety of experiences, and so our brains have developed beyond the brains of our students. This makes our think-alouds extremely valuable learning tools. Still, at times I have found myself in the middle of an inquiry lesson where I was stumped about how to differentiate the content for my learners. I walked away knowing my questions had been too vague and, while anchored in the right mindset, had done little to push my learners through their zones of proximal development.

One of the first supporting documents I created for Cubelets educators was our Questioning Guide. It’s anchored to Bloom’s Taxonomy, but the trick is to launch our questioning from the mid-point: Apply.

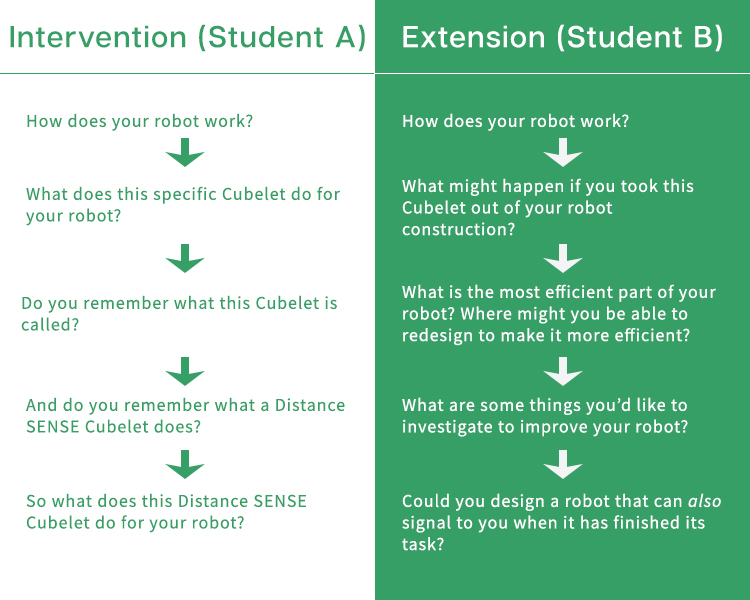

When students are working in Makerspaces or developing the foundations of an inquiry unit, they already have some background knowledge and are, in fact, applying that understanding to shape the next steps of their investigations. By starting our questioning at a mid-level like Apply, we also now have several levels of intervention and extension questions available. For example:

These questioning strategies probably feel pretty familiar because using Bloom’s Taxonomy is a well-known classroom best practice. Asking scaffolded, intentional questions allows us to differentiate learning in real time and continue to support all of our students in a way that keeps them in charge of their learning.

Now let’s take differentiation a little deeper. Fisher & Frey have recently introduced the concept of scaffolded language in a more formal way. They label the scaffolds as Questions, Prompts, and Cues. If we examine the Cubelets Questioning Guide through the lens of Fisher & Frey, we get a whole different self-evaluation of how we’re supporting students during their STEM learning. Questions, Prompts, and Cues are intended to be used in that order with students. They are designed to be interventional with the definitions of each being as follows.

Questions are open-ended and specifically do not push students in a specific direction. Notice our first question in the two examples above:

Question: How does your robot work?

- STUDENT A: My robot lights up when something gets close to it. Like an alarm or a warning.

- STUDENT B: When this Distance SENSE Cubelet sees an object get closer, it sends a message to the Flashlight ACT Cubelet above it to turn on. So it acts like an alarm or a warning.

Prompts are intended to push students toward a specific thinking or metacognitive process. For instance, in a math or science classroom, I’d be trying to draw out more specific, quantitative observations from my students. So the prompt could be:

Prompt: What does this specific Cubelet do for your robot?

- STUDENT A: This Cubelet is the one that’s looking for objects getting too close.

- STUDENT B: This is the Distance SENSE Cubelet. The closer an object gets, the higher the data value it sends to its Cubelet neighbors. Higher numbers make the flashlight brighter.

The reason for this prompt is because, in our Math/Science example, the student learning goals are quantitative and focused on gathering specific data through observations. Therefore details and specificity are key. This prompt helps redirect Student A to the learning targets driving our Cubelets investigation and gives me the valuable data I need to assess what their next steps might be. In this case, I’ll move towards a Cue to try to gather more data.

Cues are designed to point students to a specific resource or data point they are not currently using. Cues can be verbal or nonverbal. By the time students are designing, I normally like to provide them with a copy of our Cubelets Catalogue which has a picture of every Cubelet alongside its name and description. In this sample lesson, students are expected to use specific identifying language, and explain their Cubelets robots quantitatively. Therefore, I might turn to the following cue:

Cue: Do you remember what this Cubelet is called? (point at Cubelets Catalogue)

- STUDENT A: Yes, it’s the Distance SENSE Cubelet. It senses objects with an infrared sensor. Closer objects make a higher value. Objects farther away make a lower value.

The overlap between Fisher & Frey’s Guided Inquiry model and best practices during Cubelets lesson plans is direct and valuable. With the Questions, Prompts, & Cues framework in mind, you can free yourself to ask intentional (and valuable) questions in the moment with your students. And if you find some go-to questions that are especially powerful when working with Cubelets, make sure to submit them here!

Just a quick reminder – we post all of our educator resources free on the Hub. Curious about grouping or best practices with Cubelets? Need some help with Administrator Look-Fors or Progress Monitoring? It’s all there, for free, for educators, by educators.

Enjoyed this blog post? Sign up for the #CubeletsChat newsletter to receive the next blog post straight to your inbox. Plus join the discussion on twitter using the #CubeletsChat hashtag!