We just made a fairly monumental decision that almost everyone in the toy industry will tell you is asinine. We decided to build a big factory in Boulder, Colorado, and manufacture all of our products ourselves.

Electronic stuff is mostly made in China. It’s been that way for a while. Modular Robotics has a tiny factory here in Boulder, but it seemed obvious to almost everyone that as we scaled up to making millions of tiny robots each year, we’d move manufacturing to a contract manufacturer (CM) in China who would make our stuff and send us pallets of shrink-wrapped robot kits.

We have a lot of parts made for us in China. The stamped metal Cubelet connector pieces are made in Wuxi, and the plastic Cubelet shells are injection molded in Zhuhai. These parts get sent to us via UPS and we build the electronics and assemble and test everything in Boulder. It’s not trivial to get things made all the way across the world, so I’ve been visiting China once or twice a year for the last 3 years to oversee production, solve little problems on the factory floor, and audit our factories. During my most recent trip in December 2012, I visited three different CMs to begin figuring out how we might have them manufacture Cubelets (and our next product) for us.

It was a crazy few days. One CM’s mould making shop had a dirt floor. Another had ten thousand people working there and we drove through the campus in a golf cart. One had lighting so bad I could barely navigate, another had a museum of products they make that included almost every toy you might think of. But one difference between the factories struck me: at the low-end factories (they call them Tier 3), there were people everywhere. 3 workers ran each injection moulding machine, placing inserts, removing parts, trimming flash, and touching up funny white streaks with a hair dryer. The mid-level factory had fewer people, they seemed to simply have labor that was better organized to do several things at once. But at the high-end, tier 1 factories, there was nobody around. The moulding machines whizzed and klunked along on their own, aided by robotized jigs that removed parts and filled bins that ran on tracks. One worker supervised four SMT lines, simply maintaining the conveyorized, automatic machines as they did their work. China is known for its cheap labor force. Why so much automation to reduce the number of workers, I asked? The answer was simple: labor rates have increased tremendously in the last ten years.

Wait a minute. If Chinese labor costs have gotten so expensive that we need to build a robotized, automated assembly line, why would we build it in China, exactly halfway around the world, instead of in our back yard?

On the long flight home, I convinced myself that we could build our own factory, right here in Boulder, to make our tiny robots. I convinced myself that on a certain level, it’s pretty much insane to build products all of the way around the world just because the people there are poorer. I convinced myself that it would be fun, interesting, and a generally good thing to do for the world. I convinced myself to make a really unlikely decision.

There’s an alternative, by the way, that lots of companies are taking: chasing cheap labor. Huge factories are popping up in Vietnam and Thailand, Mexico, even Burma. But honestly, this seems short sighted. I don’t think it’s ethical or sustainable. I just don’t think it’s cool.

I called a couple of people that weekend to talk through the idea of manufacturing robots at scale here in the old USA. That’s where the word, “asinine” came from. A friend who works for a clothing manufacturer suggested that I must have eaten some really bad Chinese food on my trip. I was undeterred.

I’m in the unique and interesting position of being able to make big decisions for our company without giving a shit what anybody else thinks. I sort of like having that card up my sleeve but I felt like this was the wrong decision on which to play it. If we ended up building a factory in the USA just because I said so, it could quickly turn into

Eric’s Folly. It seemed dumb to make a decision like this without full consensus; otherwise, when things invariably started to go wrong, it’d be because of my stupid idea. So we formed a Manufacturing Task Force to explore the ramifications of building our robots here and not in China.

There are four of us on the task force: me, Tascha (Director of Finance), Scott (Director of Supply Chain), and Matthew (Head of Production). We bought blue terrycloth headbands that we wear both to remind ourselves of the importance of our task force and to ensure that we look like huge dorks. We’re a good mix of preconceived notions. I started out staunchly in favor of USA manufacturing, and Tascha thought it would be impossible. Scott has ten years of experience with Chinese manufacturing, and Matt, who oversees our mini-factory, was eager to expand it but admittedly a bit glassy-eyed when looking at the number of tiny robots we expect to manufacture over the next year or two. We decided to take no more than eight weeks to build out a financial model of the alternatives and see what the bottom line looked like.

The finished model is pretty complicated. I’ll break it down a bit in a future article. We took what we know about making all of the Cubelets we’ve made to date, and compared it with quotes from contract manufacturers, and projected these options out over time. That part was pretty easy; the interesting part was assigning costs to some of the “soft” metrics involved. Is it worth anything to be able to say, “Made in the USA” on our box? How much more innovative can we be with production and engineering co-located? What’s that worth? How much is the annoyance of flying for 14 hours worth over just walking downstairs? There is no straight conversion from annoyance to yuan, but we tried to put numbers on everything we could think of.

I’ll digress for a moment to let you know that I feel like data isn’t always the best answer to a question. This kills our engineers. But seriously; fundamentally we’re all ruled by predictable physics, but we can’t plan for the future at an atomic level. The “data” that we use for something like a business decision is so high-level and abstract that it can be misleading and certainly incomplete. I’m not saying that there’s magic involved, just science and causality that we don’t understand yet. Thanks Dave, for the pointer to

David Brooks’ recent article that does a much better job of explaining this than I am doing.

Even a huge amount of data can’t predict the future. But we can talk about trends and I can say confidently that I think the difference in cost between manufacturing in the USA or China is decreasing and will continue to do so. Ten years ago, it was a no-brainer; manufacturing was outsourced. But recently we’ve seen big companies like GE and Apple bring some manufacturing to the USA. I first went to China in 2008 and witnessing the change in cost and economic climate since then has made me confident that making stuff in the USA, while still not as cheap as in China, is getting much more attractive.

The last two paragraphs might sound a little bit like justification. They are. At the end of the eight weeks, we didn’t end up with a clear answer that making tiny robots in the USA would be cheaper. Nor did we end up with the opposite answer. We ended up in between. All of our soft costs were estimated as a range. If we calculated based on one side of the range, we’d end up with “do it ourselves.” If we calculated toward the other limit, we’d end up with “have a factory in China do it.” We did end up with the conclusion that we could, in fact, do it one way or the other and have a high likelihood of success.

So we decided to build a big factory and make our robots here in Boulder. Woo! The task force is into it, I’m into it, the Board of Directors is into it, and our whole team is into it. When the task force announced its decision to everyone at scrum, a couple of assembly elves even piped up spontaneously to talk about how amped they were to work for a company that made stuff they were proud of. Thanks Kristen and Joe!

We’ll keep our injection molding and metal stamping in China for now, but examine bringing them over here after we’ve figured out the other parts of our manufacturing-at-scale process. We’ve already been working on getting a stencil printer, board washer, and AOI for our SMT electronics line. We’ve hired four new employees in the last couple of weeks. And we’re looking around at big (15k square foot) manufacturing spaces in town.

It’s going to be an interesting couple of years. I’ll try to write often about how it’s going robotizing and automating our little factory. Know anyone who wants a

job building tiny robots?

I immediately thought of Jon Hiller. When I was a post-doc at the Cornell Computational Synthesis lab (now called the

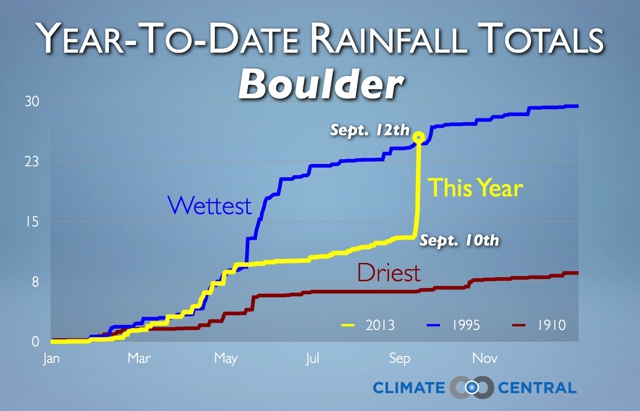

I immediately thought of Jon Hiller. When I was a post-doc at the Cornell Computational Synthesis lab (now called the  I catch a little flack around Modular Robotics sometimes because I can get get pretty excited about charts. Some people can look at huge spreadsheets of numbers and make sense of them, but I generally cannot. I usually think of data as an input, and a chart as the output. Well, anyway, take a look at the rainfall chart above!

I’m stuck in Nederland, the little mountain town West of Boulder where I live; all of the roads in and out are closed. We’re at 8,236 feet above sea level, so all’s fine here, all of our rain just washed down to Boulder. It feels a little odd not being able to leave, but we have ample stores of coffee and chocolate and also a big vegetable garden, so we’ll be just fine. It just started raining again.

If you’re interested in reading about the meteorology behind the current flooding, Bob Henson

I catch a little flack around Modular Robotics sometimes because I can get get pretty excited about charts. Some people can look at huge spreadsheets of numbers and make sense of them, but I generally cannot. I usually think of data as an input, and a chart as the output. Well, anyway, take a look at the rainfall chart above!

I’m stuck in Nederland, the little mountain town West of Boulder where I live; all of the roads in and out are closed. We’re at 8,236 feet above sea level, so all’s fine here, all of our rain just washed down to Boulder. It feels a little odd not being able to leave, but we have ample stores of coffee and chocolate and also a big vegetable garden, so we’ll be just fine. It just started raining again.

If you’re interested in reading about the meteorology behind the current flooding, Bob Henson

Some of these tests require that we send a few boxes of Cubelets off to a special lab to get certified. Some of the tests can be done ourselves. Either way, we need to know the standards so that we make sure our designs comply long before we actually send something in for its official test. Know what irks me? That these tests are not posted online for free access. The ASTM test is $72. Each of the EU tests is $300!

Sometimes it’s super-expensive to send Cubelets out to be tested. For some recent testing toward the CE mark, we got quotes ranging from $8,000 to $27,000. I’m OK with both the cost (it takes a tremendous amount of time to test products thoroughly) and the requirements that certified, external labs do the testing. But the standards? They should be freely available to inventors, tinkerers, and grandparents so that they too can have the broadest possible impact.

If I were in charge, I’d change the mission of the toy safety committies to: “Make toys safer.” Putting the recipes for how to do this behind a ridiculous paywall doesn’t help to achieve that mission at all.

Some of these tests require that we send a few boxes of Cubelets off to a special lab to get certified. Some of the tests can be done ourselves. Either way, we need to know the standards so that we make sure our designs comply long before we actually send something in for its official test. Know what irks me? That these tests are not posted online for free access. The ASTM test is $72. Each of the EU tests is $300!

Sometimes it’s super-expensive to send Cubelets out to be tested. For some recent testing toward the CE mark, we got quotes ranging from $8,000 to $27,000. I’m OK with both the cost (it takes a tremendous amount of time to test products thoroughly) and the requirements that certified, external labs do the testing. But the standards? They should be freely available to inventors, tinkerers, and grandparents so that they too can have the broadest possible impact.

If I were in charge, I’d change the mission of the toy safety committies to: “Make toys safer.” Putting the recipes for how to do this behind a ridiculous paywall doesn’t help to achieve that mission at all.  I woke up and looked out the open sides of our little thatch-roofed cabin to see the moonlight flickering on the ocean swell as it rolled lazily onto the beach. The thought occurred to me that Modular Robotics was happily functioning while I was gone. We’ve put together such a great team that I’m not even really necessary for day-to-day functioning of the company. I can leave, turn off my phone for a week, and we keep pumping out Cubelets.

If I think about our company as a little train, we’ve built the train cars, loaded up on fuel, figured out how to mix drinks in the bar car, and left the station. It will happily chug along for a while without the need for me to walk up and down its length chatting with passengers and crew and patrolling for problems. I suppose that I could even just get off the train more often, and I probably will. The realization here was more profound, though. With the train carrying on smoothly, I’m free to head to the caboose, pull out some maps, do some reading, and determine where I think the train should go.

I’m the CEO. It probably seems obvious to you that my role should focus primarily on strategy and direction. While that seems fairly obvious to me in the abstract, it took a little time away and a different setting to make it seem real in the present. I think the reason for my slow uptake has everything to do with our growth. When there were two of us, I designed circuits and sourced magnets and wrote code. When there were ten, I answered questions and did a lot of hiring and wrangled our bookkeeping. Strategy and direction happened at interstitial times: at night, over a meal, or during a flight. Over the last couple of years we’ve made hires sequentially, and each new team member has taken a role that I muddled through, and filled it fully and expertly. Now that the train is rolling, our next hire is someone to focus not on operations, but on strategy, new products, team building, and design. That hire is me!

I woke up and looked out the open sides of our little thatch-roofed cabin to see the moonlight flickering on the ocean swell as it rolled lazily onto the beach. The thought occurred to me that Modular Robotics was happily functioning while I was gone. We’ve put together such a great team that I’m not even really necessary for day-to-day functioning of the company. I can leave, turn off my phone for a week, and we keep pumping out Cubelets.

If I think about our company as a little train, we’ve built the train cars, loaded up on fuel, figured out how to mix drinks in the bar car, and left the station. It will happily chug along for a while without the need for me to walk up and down its length chatting with passengers and crew and patrolling for problems. I suppose that I could even just get off the train more often, and I probably will. The realization here was more profound, though. With the train carrying on smoothly, I’m free to head to the caboose, pull out some maps, do some reading, and determine where I think the train should go.

I’m the CEO. It probably seems obvious to you that my role should focus primarily on strategy and direction. While that seems fairly obvious to me in the abstract, it took a little time away and a different setting to make it seem real in the present. I think the reason for my slow uptake has everything to do with our growth. When there were two of us, I designed circuits and sourced magnets and wrote code. When there were ten, I answered questions and did a lot of hiring and wrangled our bookkeeping. Strategy and direction happened at interstitial times: at night, over a meal, or during a flight. Over the last couple of years we’ve made hires sequentially, and each new team member has taken a role that I muddled through, and filled it fully and expertly. Now that the train is rolling, our next hire is someone to focus not on operations, but on strategy, new products, team building, and design. That hire is me!  Thanks for the photo, Sawyer!

Thanks for the photo, Sawyer!