We’ve been delaying the date that we think we’re going to ship our first Cubelets kits for months now, and it’s driving us crazy. It’s annoying other people as well, and I’m sorry for that.

I studied architecture in college, but have worked mostly on software projects since then. While software isn’t always easy, it can certainly be fast. Especially now that much software is internet-based, programmers can easily iterate, fix problems, and release new versions quickly. Most architecture projects are the opposite: five years from idea to final construction isn’t out of the ordinary. Although I originally had a thought that Cubelets manufacturing could be agile and more like software production, it’s clearly more like an architecture project, and in fact it’s been about five years since we started.

We received an enormous box full of thousands of tiny magnets yesterday, and they were all about 0.2mm too long. This seems like a tiny amount, but since our magnets are cast into the plastic Cubelet shells, magnets that are too long prevent the injection mold from fully closing and can also scratch the expensive mold badly. These custom magnets came after working with the supplier for three months to get the design just perfect. We’ll have to either shave down every magnet and re-plate it, or make a new batch which takes 2 weeks. It’s the little problems like this that multiply for Modular Robotics. There are 300 different parts in each Cubelet kit, many of them custom, from almost 100 different suppliers. And since assembly happens in sequential steps, each problem holds up the process. We’ve already sorted out problems like wheels that were too small, metal parts with lead in them, faulty LEDs, and spontaneously discontinued electronic parts. I never even imagined that something like an earthquake in Japan would influence our production. Although we’re successfully solving each new problem as it comes up, we’re going slower than we hoped.

We’ve finished building circuit boards for the first 100 Cubelets kits and the software is tested and ready. When we have all of our custom-made parts in hand and can begin mechanical assembly, I’ll be able to update this post with a revised shipping date. Meanwhile, thanks for joining us on this exciting little journey.

Recently, I was having a hard time deciding what to do about packaging for our first small production runs of Cubelets. I could only see two options, and both were bad. The dilemma involved either hiring a firm to design the packaging (at a cost we couldn’t afford) or doing it ourselves (which we are not particularly good at). Mark came up with the idea of holding a competition. Designers would submit entries and we would pick a winner, rewarding the designer with cash, Cubelets, and instant fame. A perfect third solution.

Later, in conversation, somebody mentioned that we were crowdsourcing our packaging design and I feel obligated to clarify. In my mind, crowdsourcing relies on the wisdom of the crowd itself, the power of collective opinion, even democracy. Crowdsourcing implies that we would use whatever packaging design that the crowd wants, which we are emphatically not doing. We are soliciting entries from individuals in the crowd, then we are deciding which one we want to use.

Democracy is a great way to structure government. But design shouldn’t be crowdsourced. Are a thousand naive voices better or more valid than one thoughtful designer’s? Probably not.

It might seem fiddly to make this distinction between the wisdom of the crowd and the wisdom of a single, particularly good designer in the crowd. But this is something that we’re trying hard to teach with Cubelets. Today in the media, we’re seeing a lot of oversimplification — phrases like “society has a negative view about…” or “America voted for….” I think these are poisonous ways to think about the world. Society has no views: certain individuals do (but others don’t). America didn’t vote: Americans did, and many of them probably voted the other way. By generalizing and refusing to look deeper at the complexities that cause some emergent phenomenon, we’ll never be able to solve (or even understand) the really big problems in the world.

Although Cubelets are a little behind schedule for manufacturing, we thought you might enjoy a quick video of our latest prototypes. Production Cubelets will be in

fancy colors, these are our top-secret ninja version.

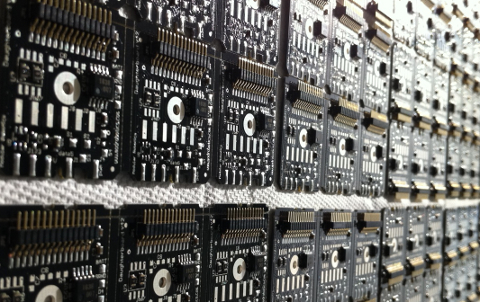

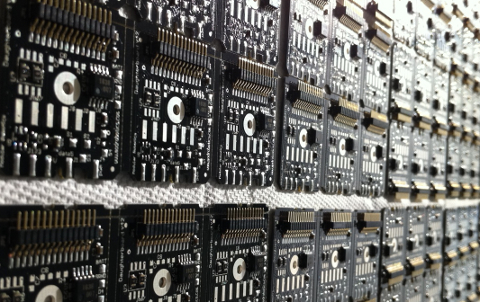

When I was a kid, I remember hearing about an inspired teacher who tried to convey how large a million is by dropping a million kernels of popcorn on his students from some trap doors in the ceiling. I always secretly wished that one of

my teachers would do the same thing. Would a million popcorns cover the floor? Would they be a foot deep? In case you’re curious about how much 10,000 tiny circuit boards is, I’m happy to report: they’ll almost bury you! If you’re sitting in a very tiny room.

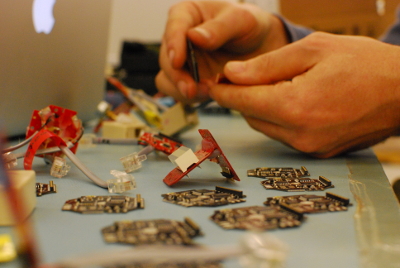

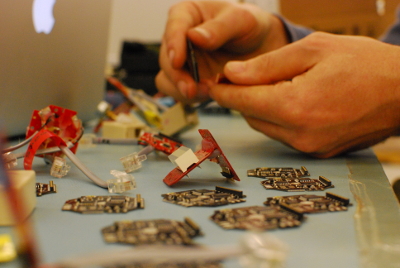

We used a robot to place the components on our earlier run of 2000 circuit boards, but we placed components on the rest of the boards ourselves, with tweezers, here in Boulder, Colorado. We look like a little factory these days. Eric will be in China at the end of January retrieving the plastic pieces we need to assemble complete Cubelets and they’ll be available soon after that!

We made 2000 tiny circuit boards this weekend!

We used a giant robot; it’s called a

Pick and Place machine because it picks up each tiny electronic component from it’s package and places it perfectly on the circuit board. It’s fast, accurate, and fun to watch (for a little while).

Robot Assembly – Pick and Place

It’s exciting to see Cubelets coming together. Only 10,000 more circuit boards to go!

Cubelets

Cubelets are little robotic blocks that you can snap together to make bigger robots that drive around, do smart things, and act like they’re alive. With no programming involved, Cubelets are totally different from other robotic construction kits. Each little cube talks to its neighbors, and in the same way that flocks of birds can end up doing surprising things, robotic actions emerge from all of the interacting cubes.

I’ve been working on this project since 2006 so I’m pretty excited to finally unveil the kit’s new name and logo. The kit used to be called roBlocks, but there was some trademark hassle.

Moxie Sozo, a Boulder-based graphic design studio, did this fantastic logo design for us. Gorgeous web site coming soon.

We’ll have kits for sale on

www.modrobotics.com before the end of this year!

We just moved Modular Robotics into a great new space in downtown Boulder, Colorado. If you’re local, come visit us at 2500 Pearl Street, right above Mike’s Camera. It’s no coincidence that our new building is in the shape of a cube. If you squint, you can see Mark through the window, and also the mad style of our old-doors-on-sawhorses work tables. And look – there’s UPS ready to bring our robots right to you.

We’re pleased to announce the award of a two-year $486,906 grant from the US National Science Foundation’s Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR Phase II) program. The grant project is called “Learning About Complexity through Programming Modular Robots” and it’s for our work developing a system through which kids interact with our modular robot kits. You can read the

abstract at the NSF or take a look at our

formal press release.

One great thing about this grant is that it will let us speed up. Until now, we’ve been running Modular Robotics on a very tight budget with a very small team. Our prototypes are still assembled in Eric’s garage. The SBIR funding will allow us to hire three more people, move into a “real” studio, and make many more robots much more quickly.

Another great thing is that it will let us slow down. Like any small business, we’ve been a little harried recently. We’ve been trying to get our robot kit out the door as quickly as possible before we run out of money. It’s expensive to make lots of tiny robots, so we’ve been making a lot of compromises in our rush to get something available. Although we’re still going to have a first round of robot kits available this summer, the grant funding allows us to pay attention to the fine details of the design and make sure we’re releasing our robots thoughtfully and deliberately.

Anyway, we’re thrilled. Coming soon: thousands and thousands of tiny robots.

Since we’re getting close to firing up the injection molder for our first run of commercial blocks, we’ve been thinking a lot about color. We use color to differentiate the different blocks by function, and we want the colors to both make sense and look cool when the blocks are assembled into a robot. In our research prototypes we made Action blocks white, Sense blocks black, and used rainbow colors for the rest. The rainbow just happened because of the material colors that were available for the Stratasys 3D printer we were using — it seemed a little too young, like how the color and scale of

Duplo makes it obvious that it’s for little kids. And the white got dirty easily.

For our first run, Sense blocks will still be black, but Action blocks will be transparent. The transparent cubes look great (they remind me of

Capsela) and we’ll be posting some new photos shortly. And we’re settling on the color palette shown above for the Think and Utility blocks. It’s not a rainbow but the colors are easy to differentiate. It’s a little earthy, and since Passive blocks will be green, may even make a robot look a little bit

natural.

We’ve been awfully excited to use 100% recycled plastic for the shells of our robotic construction kit. We were going to end up using two materials for the blocks: black recycled ABS and clear recycled PET (from soda bottles). Using materials that have already been around the block and into the bin made us feel better about our contribution to the mountain of stuff around us. And that’s why it’s pretty upsetting to find out that we probably cannot use recycled plastic at all.

In 2008, the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) was signed into law in the US. Don’t get us wrong, the law is a good thing: it protects kids from lead and other harmful substances in toys, and requires mandatory third party testing for all children’s products. One important group of substances regulated by the new law is phthalates, which are chemicals added to plastic during manufacturing to make them more flexible and durable. Heavy exposure to phthalates, unfortunately, has been shown to cause endocrine disruption and infertility.

To comply with the CPSIA, our plastic must meet a certain requirement for phthalate levels. But since recycled plastics are just a mix of old plastics ground up and reheated, no supplier will guarantee that every part will meet the requirements. So while we haven’t given up on our search for a better option, unfortunately it looks like our only option is to use virgin plastic. Any thoughts?

We’ve been delaying the date that we think we’re going to ship our first Cubelets kits for months now, and it’s driving us crazy. It’s annoying other people as well, and I’m sorry for that.

I studied architecture in college, but have worked mostly on software projects since then. While software isn’t always easy, it can certainly be fast. Especially now that much software is internet-based, programmers can easily iterate, fix problems, and release new versions quickly. Most architecture projects are the opposite: five years from idea to final construction isn’t out of the ordinary. Although I originally had a thought that Cubelets manufacturing could be agile and more like software production, it’s clearly more like an architecture project, and in fact it’s been about five years since we started.

We received an enormous box full of thousands of tiny magnets yesterday, and they were all about 0.2mm too long. This seems like a tiny amount, but since our magnets are cast into the plastic Cubelet shells, magnets that are too long prevent the injection mold from fully closing and can also scratch the expensive mold badly. These custom magnets came after working with the supplier for three months to get the design just perfect. We’ll have to either shave down every magnet and re-plate it, or make a new batch which takes 2 weeks. It’s the little problems like this that multiply for Modular Robotics. There are 300 different parts in each Cubelet kit, many of them custom, from almost 100 different suppliers. And since assembly happens in sequential steps, each problem holds up the process. We’ve already sorted out problems like wheels that were too small, metal parts with lead in them, faulty LEDs, and spontaneously discontinued electronic parts. I never even imagined that something like an earthquake in Japan would influence our production. Although we’re successfully solving each new problem as it comes up, we’re going slower than we hoped.

We’ve finished building circuit boards for the first 100 Cubelets kits and the software is tested and ready. When we have all of our custom-made parts in hand and can begin mechanical assembly, I’ll be able to update this post with a revised shipping date. Meanwhile, thanks for joining us on this exciting little journey.

We’ve been delaying the date that we think we’re going to ship our first Cubelets kits for months now, and it’s driving us crazy. It’s annoying other people as well, and I’m sorry for that.

I studied architecture in college, but have worked mostly on software projects since then. While software isn’t always easy, it can certainly be fast. Especially now that much software is internet-based, programmers can easily iterate, fix problems, and release new versions quickly. Most architecture projects are the opposite: five years from idea to final construction isn’t out of the ordinary. Although I originally had a thought that Cubelets manufacturing could be agile and more like software production, it’s clearly more like an architecture project, and in fact it’s been about five years since we started.

We received an enormous box full of thousands of tiny magnets yesterday, and they were all about 0.2mm too long. This seems like a tiny amount, but since our magnets are cast into the plastic Cubelet shells, magnets that are too long prevent the injection mold from fully closing and can also scratch the expensive mold badly. These custom magnets came after working with the supplier for three months to get the design just perfect. We’ll have to either shave down every magnet and re-plate it, or make a new batch which takes 2 weeks. It’s the little problems like this that multiply for Modular Robotics. There are 300 different parts in each Cubelet kit, many of them custom, from almost 100 different suppliers. And since assembly happens in sequential steps, each problem holds up the process. We’ve already sorted out problems like wheels that were too small, metal parts with lead in them, faulty LEDs, and spontaneously discontinued electronic parts. I never even imagined that something like an earthquake in Japan would influence our production. Although we’re successfully solving each new problem as it comes up, we’re going slower than we hoped.

We’ve finished building circuit boards for the first 100 Cubelets kits and the software is tested and ready. When we have all of our custom-made parts in hand and can begin mechanical assembly, I’ll be able to update this post with a revised shipping date. Meanwhile, thanks for joining us on this exciting little journey.  We’ve been delaying the date that we think we’re going to ship our first Cubelets kits for months now, and it’s driving us crazy. It’s annoying other people as well, and I’m sorry for that.

I studied architecture in college, but have worked mostly on software projects since then. While software isn’t always easy, it can certainly be fast. Especially now that much software is internet-based, programmers can easily iterate, fix problems, and release new versions quickly. Most architecture projects are the opposite: five years from idea to final construction isn’t out of the ordinary. Although I originally had a thought that Cubelets manufacturing could be agile and more like software production, it’s clearly more like an architecture project, and in fact it’s been about five years since we started.

We received an enormous box full of thousands of tiny magnets yesterday, and they were all about 0.2mm too long. This seems like a tiny amount, but since our magnets are cast into the plastic Cubelet shells, magnets that are too long prevent the injection mold from fully closing and can also scratch the expensive mold badly. These custom magnets came after working with the supplier for three months to get the design just perfect. We’ll have to either shave down every magnet and re-plate it, or make a new batch which takes 2 weeks. It’s the little problems like this that multiply for Modular Robotics. There are 300 different parts in each Cubelet kit, many of them custom, from almost 100 different suppliers. And since assembly happens in sequential steps, each problem holds up the process. We’ve already sorted out problems like wheels that were too small, metal parts with lead in them, faulty LEDs, and spontaneously discontinued electronic parts. I never even imagined that something like an earthquake in Japan would influence our production. Although we’re successfully solving each new problem as it comes up, we’re going slower than we hoped.

We’ve finished building circuit boards for the first 100 Cubelets kits and the software is tested and ready. When we have all of our custom-made parts in hand and can begin mechanical assembly, I’ll be able to update this post with a revised shipping date. Meanwhile, thanks for joining us on this exciting little journey.

We’ve been delaying the date that we think we’re going to ship our first Cubelets kits for months now, and it’s driving us crazy. It’s annoying other people as well, and I’m sorry for that.

I studied architecture in college, but have worked mostly on software projects since then. While software isn’t always easy, it can certainly be fast. Especially now that much software is internet-based, programmers can easily iterate, fix problems, and release new versions quickly. Most architecture projects are the opposite: five years from idea to final construction isn’t out of the ordinary. Although I originally had a thought that Cubelets manufacturing could be agile and more like software production, it’s clearly more like an architecture project, and in fact it’s been about five years since we started.

We received an enormous box full of thousands of tiny magnets yesterday, and they were all about 0.2mm too long. This seems like a tiny amount, but since our magnets are cast into the plastic Cubelet shells, magnets that are too long prevent the injection mold from fully closing and can also scratch the expensive mold badly. These custom magnets came after working with the supplier for three months to get the design just perfect. We’ll have to either shave down every magnet and re-plate it, or make a new batch which takes 2 weeks. It’s the little problems like this that multiply for Modular Robotics. There are 300 different parts in each Cubelet kit, many of them custom, from almost 100 different suppliers. And since assembly happens in sequential steps, each problem holds up the process. We’ve already sorted out problems like wheels that were too small, metal parts with lead in them, faulty LEDs, and spontaneously discontinued electronic parts. I never even imagined that something like an earthquake in Japan would influence our production. Although we’re successfully solving each new problem as it comes up, we’re going slower than we hoped.

We’ve finished building circuit boards for the first 100 Cubelets kits and the software is tested and ready. When we have all of our custom-made parts in hand and can begin mechanical assembly, I’ll be able to update this post with a revised shipping date. Meanwhile, thanks for joining us on this exciting little journey.

When I was a kid, I remember hearing about an inspired teacher who tried to convey how large a million is by dropping a million kernels of popcorn on his students from some trap doors in the ceiling. I always secretly wished that one of my teachers would do the same thing. Would a million popcorns cover the floor? Would they be a foot deep? In case you’re curious about how much 10,000 tiny circuit boards is, I’m happy to report: they’ll almost bury you! If you’re sitting in a very tiny room.

We used a robot to place the components on our earlier run of 2000 circuit boards, but we placed components on the rest of the boards ourselves, with tweezers, here in Boulder, Colorado. We look like a little factory these days. Eric will be in China at the end of January retrieving the plastic pieces we need to assemble complete Cubelets and they’ll be available soon after that!

When I was a kid, I remember hearing about an inspired teacher who tried to convey how large a million is by dropping a million kernels of popcorn on his students from some trap doors in the ceiling. I always secretly wished that one of my teachers would do the same thing. Would a million popcorns cover the floor? Would they be a foot deep? In case you’re curious about how much 10,000 tiny circuit boards is, I’m happy to report: they’ll almost bury you! If you’re sitting in a very tiny room.

We used a robot to place the components on our earlier run of 2000 circuit boards, but we placed components on the rest of the boards ourselves, with tweezers, here in Boulder, Colorado. We look like a little factory these days. Eric will be in China at the end of January retrieving the plastic pieces we need to assemble complete Cubelets and they’ll be available soon after that!

Since we’re getting close to firing up the injection molder for our first run of commercial blocks, we’ve been thinking a lot about color. We use color to differentiate the different blocks by function, and we want the colors to both make sense and look cool when the blocks are assembled into a robot. In our research prototypes we made Action blocks white, Sense blocks black, and used rainbow colors for the rest. The rainbow just happened because of the material colors that were available for the Stratasys 3D printer we were using — it seemed a little too young, like how the color and scale of

Since we’re getting close to firing up the injection molder for our first run of commercial blocks, we’ve been thinking a lot about color. We use color to differentiate the different blocks by function, and we want the colors to both make sense and look cool when the blocks are assembled into a robot. In our research prototypes we made Action blocks white, Sense blocks black, and used rainbow colors for the rest. The rainbow just happened because of the material colors that were available for the Stratasys 3D printer we were using — it seemed a little too young, like how the color and scale of